Climate migration: There may be no traditional way of life for these children but there is hope

Over the past decade 1.7 million people have migrated away from Vietnam’s Mekong Delta.

It’s happened against a backdrop of falling crop yields – a situation blamed on rising levels of saltwater and freshwater droughts.

Homes have literally fallen into the sea. Elsewhere land has been lost forever. Recent reports suggest, within half a century, 12 million people in the Mekong Delta alone are likely to be displaced by flooding. Most will head for cities. Many will replace rural farming with urban factory work.

In Mongolia, the majority of the population has traditionally lived a nomadic lifestyle. Families herded animals and lived off the land. But the country has seen temperatures rise by 4 degrees Fahrenheit in the past 70 years. The Gobi Desert expands northwards by around 4 miles a year, further limiting pasture land. Extreme weather has become the norm.

With a population of just over three million, each year thousands more move to the country’s one major city, Ulaanbaatar. There, around 62% of the population now live in ger districts – without running water, paved roads or refuse collection.

People don’t take the decision to migrate easily. It’s frequently an act of desperation. Migration usually means losing wider support networks of extended family and community, and young children are especially vulnerable to that loss.

In Vietnam and Mongolia, hundreds of thousands of children each year are brought along to cities by migrating parents in search of work. But, on arrival, these families struggle to find safe and nurturing child care while parents work long shifts.

With this in mind, in 2017 OneSky opened an Early Learning Centre to serve migrant children whose parents are employed in the surrounding factory zone of Da Nang, Vietnam. And now, we’ve begun training the home-based daycare providers who lack education, materials and support but are often the only option for low wage families in the city.

Meanwhile in Mongolia, formerly nomadic families find transitioning to life in the city equally difficult. Low employment, high levels of alcoholism and the lack of a cultural emphasis on community results in fractured families.

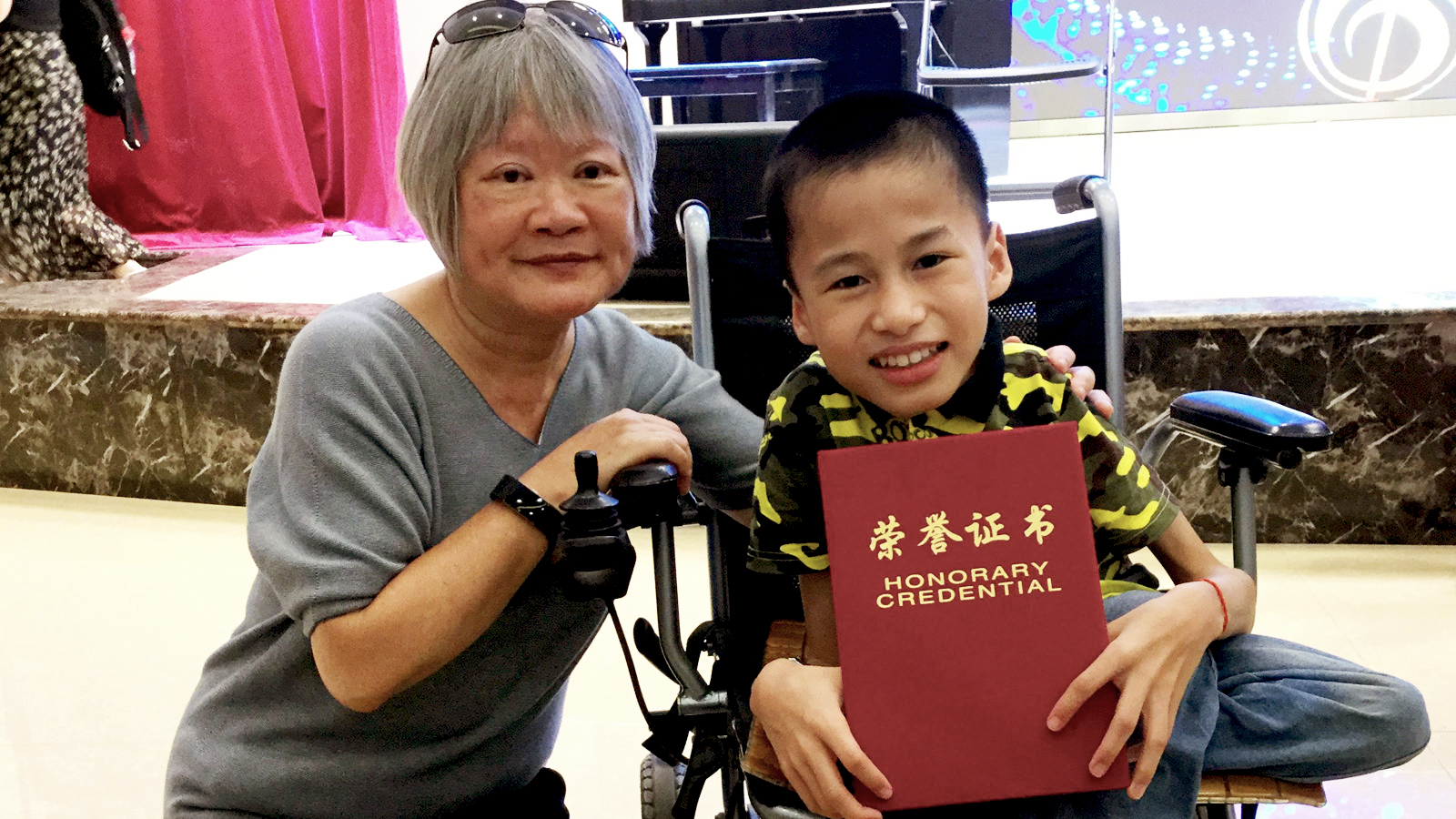

OneSky began our work in that nation’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, with a small project in a state-run day nursery. There we brought the OneSky Approach to 180 very young children. These children had been referred as a result of nutritional deficiencies. However, beyond nutrition little attention was previously paid to social and emotional needs.

OneSky hired and trained additional caregivers to provide responsive care. Rooms were refurbished and age-appropriate toys were made available. Now we want to do more.

Climate change is destroying the traditional way of life in Mongolia, but we believe there’s a way to create community care systems that support young children while creating employment opportunities for women in search of work.

Late last year, the OneSky Early Learning Center in Vietnam closed for a day following the worst rains ever recorded in Da Nang. Much of the city was underwater.

It was a reflection of the professionalism of staff who braved flooding to re-open the following day. We know how much we are needed.

But it was also a reminder. There are no escapes from the effects of climate change. It will continue to dictate who needs our help and how we work.

This week we see children playing a key role in global climate strikes to remind us it’s their future. Likewise, those who suffer forced migration as a result of climate must not be written off.

Our young people will grow up in a fast-changing, very different world. We need to listen to them now and we need to equip them to benefit their communities.

Our planet needs them all.